Coronavirus

Coronavirus Pandemic: The World Could Learn from Japan – If It Only Wanted

Japan’s focus on the 3Cs instead of large-scale testing was met with disbelief in the West; global excess mortality numbers now tell a different story.

Published

2 years agoon

Japan’s early focus on ventilation and the 3Cs is one of its key features in its pandemic flight. New data seems to confirm it gets a lot right.

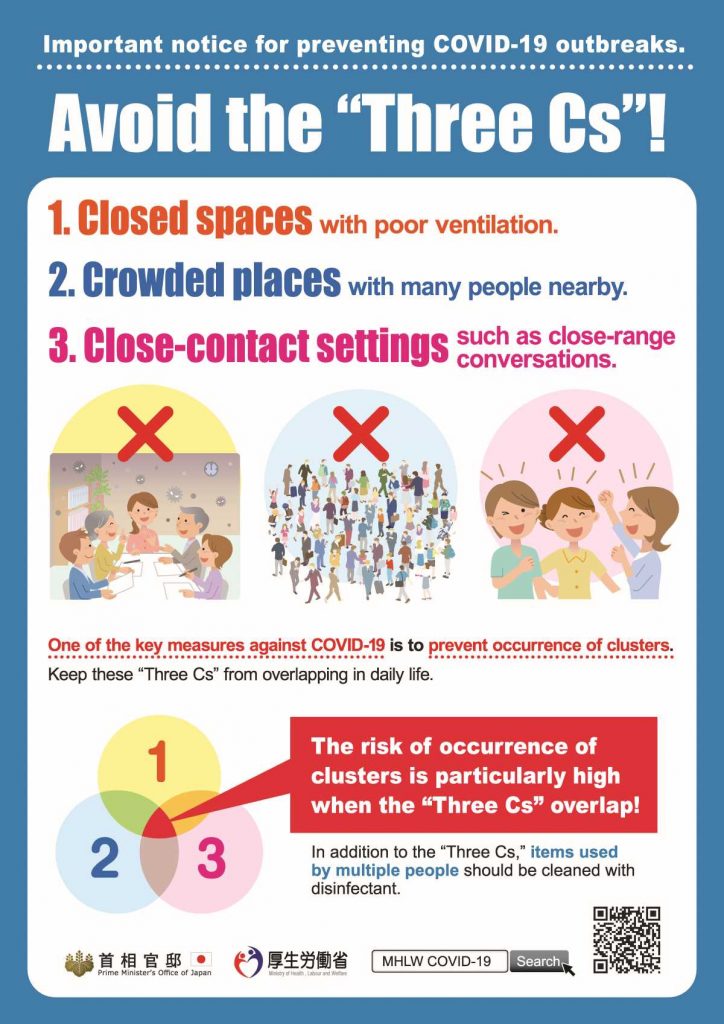

In early March 2020 the Japanese government came up with a simple message. Avoid the 3Cs – closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings. It was a puzzling announcement compared to harsh measures adopted in many other countries to fight the outbreak of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

Around the same time, New Zealand, a nation of about 5 million, made its population stay at home for four weeks. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern warned those violating the compulsory stay-at-home rules that they would face “no tolerance”. “We will not hesitate to use our enforcement powers if needed.”

New Zealand was not alone. In March 2020 many other countries went into lockdown, imposed curfews, limited physical contact and closed their borders. In places like Spain, the army patrolled empty streets to enforce the government’s stay at home order. Employees of Sydney Aquarium brought their dogs to the closed venue in mid-April to entertain the fish.

Japan: Another Approach

In contrast, Japan’s response stood out. Regarded by many as slow, bureaucratic and out of touch, it raised fears that the country could see record infection cases with a high death toll, given it has the world’s oldest population.

Particularly, Japan’s refusal to do any large-scale testing like most other Western countries was met with disbelief. Epidemiologists and public health experts argued this was putting the country into a fly by night situation, leaving little guidance to indicate how the pandemic was evolving.

Excess Mortality

However, more than two years after the WHO declared the global outbreak a pandemic, there is mounting evidence that Japan got many things right.

According to a study by the World Health Organization (WHO) Japan is one of the few countries that did not report any excess mortality for the pandemic years 2020 and 2021. The WHO estimates that globally, around 13.3 to 16.6 million additional people died because of the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, about 2.7 times more than officially recorded deaths.

Excess death toll serves as an important figure to gauge the severity of an infection wave. It counts all reported deaths and compares them to the number that we would expect under normal circumstances.

According to the WHO estimate, Germany had about 200,000 excess deaths in 2020 and 2021 that could directly or indirectly be linked to the pandemic. The United States comes in at around 933,000 excess deaths, and India tops the list with 4.74 million excess deaths.

In contrast, Japan comes in at minus 19,471 during the two years.

How Japan Compares

Only very few countries kept excess deaths close to or even below zero. Apart from Japan the group includes Norway, Australia, Iceland, Mongolia and New Zealand.

“Being rich and geographically isolated helps,” Francois Balloux, chair in computational biology systems at University College London Genetics Institute, recently commented in The Guardian.

But Balloux might not have realized what an outlier Japan is on this list. Densely populated and with the oldest population in the world, it never imposed lockdowns or any other harsh measures, did not do mass testing, and still fared pretty well.

Instead of mandates and rules, Japan only relied on recommendations. Wear a mask, avoid the three Cs, improve ventilation and air hygiene, wash your hands and stay at home if you have a fever. And it kept to its simple message for more than two years.

Badly explained at the time, however, was the strategy behind Japan’s unique response.

The Cruise Ship Saga

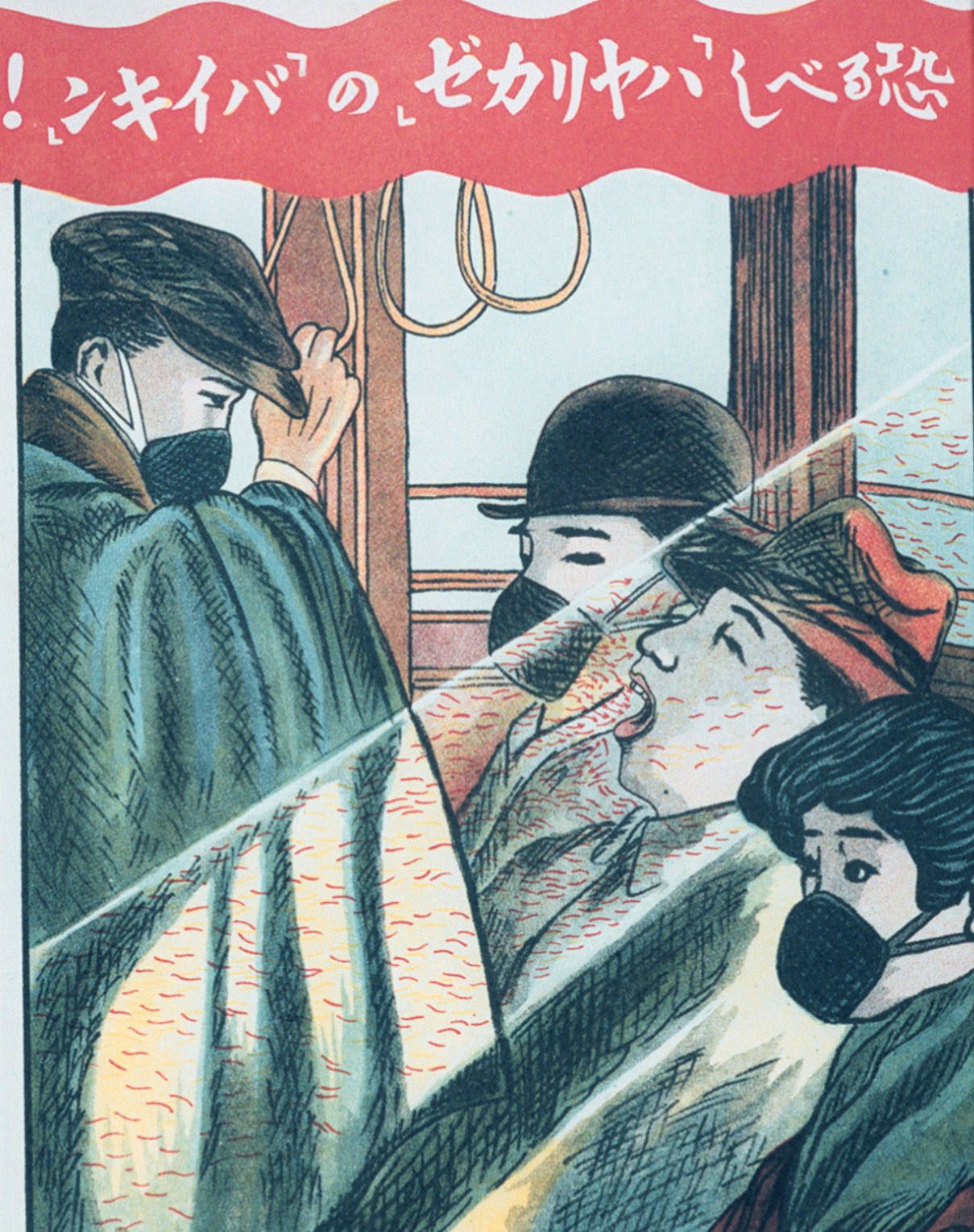

When virologist Hitoshi Oshitani from Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine in Sendai, observed the outbreak on the Diamond Princess cruise ship in February 2020, he noticed a couple of unusual things. While the disease-stricken ship with 3,711 passengers on board had been quarantined off Daikaku pier at Yokohama port, the number COVID cases on board were steadily mounting.

Soon more than half a dozen quarantine officers caught the virus on the ship, despite protective measures like gloves and gowns. This made Oshitani and his team suspect that the virus was transmitted in an unusual way.

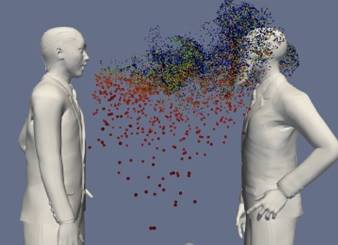

“The quarantine officers, they’re professionals, they know how to protect themselves,” Oshitani remarked at the time. The scientist, who had studied the SARS virus outbreak in China in 2002, suspected this novel coronavirus could be spreading through microdroplets, tiny particles floating the the air, also known as “aerosols.”

Another surprise was that about half of the 712 positive cases on board the Diamond Princess were completely asymptomatic. The mystery only widened when Oshitani found out that the virus was also spread by infected people before symptoms appeared, or by infected people who never developed any symptoms.

This made it very tricky to monitor the virus. “The transmission chain becomes invisible, completely off our radar,” Oshitani stated then.

Adding to the list of surprises, the virus also spread unevenly. Almost 80 percent of the infected people on board the cruise ship weren’t passing on the virus to anyone else at all. Instead, a small minority of people infected many others at the same time, often in crowded, poorly ventilated spaces where they were in close contact with each other.

Slowing the Speed

The Diamond Princess served as a petri dish for Japanese researchers. Considering Oshitani´s findings they concluded that eliminating the virus would be almost impossible.

Instead, the Japanese strategy was “to slow the speed of the expansion” of the outbreak. This was explained by Shigeru Omi, a public health specialist and head of the Japan Community Health Care Organization, in a press briefing in March 2020.

One of the ways to contain the virus was to concentrate on settings where one person could spread the virus to many people. Thus, Japan’s three Cs were born. Avoid closed spaces, crowded places and close-contact settings.

Oshitani and his colleagues were way ahead of everyone else with their assessment. It took the WHO months to declare that the virus was airborne. The failure to recognize its mode of transmission early on led to ill-advised guidance that mask wearing was basically useless in a normal social setting. It took months to correct this.

Clear Messaging

The fiasco over the cruise ship led Oshitani and other researchers in Japan to draw the right conclusions, and it helped Japan fight the pandemic well. However, at the same time it tainted Japan’s handling of the crisis.

To this day, Japan's success is mostly seen as mysterious, random and somehow inexplicable. Instead of recognizing its success, Japan is accused of hiding its true death toll, not testing enough to keep counts low and prioritizing holding the Olympic Games in Tokyo in 2021 instead of fighting the virus through the same tough measures everyone else adopted.

But months before the rest of the world woke up to masks and the dangers of confined spaces and dense crowds, Japan set out to find a way to live through the pandemic without imposing draconian rules. Restaurants opened their windows and spaced out customers. Shops placed assistants behind plastic screens. Bars closed early, while singing and cheering was discouraged.

Air filters, air humidifiers and C02 monitors appeared at restaurants and public buildings and soon became common features. Much has stayed that way. Subway trains in Japan have been operating with open windows for more than two years now.

As it turns out, clear communication – three Cs - were a lot easier to understand than the confusing back-and-forth guidance in Western countries. The Western guidance on mask wearing moved from not necessary, to necessary, to mandate, to better masks with higher filtration, to masks in certain settings only, to no masks, then reverted to masks again.

There is no indication that Japan will ditch wearing masks anytime soon. Most likely, when autumn arrives and cases rise again, many other countries will have to update their mask guidance. They all could learn a couple of things from Japan if they wanted.

RELATED:

- EDITORIAL | In Possible 7th COVID-19 Wave, Japan Must Protect the Elderly

- The COVID-19 Olympics 2.0: How the Beijing Games Compare to the Tokyo Games

- Learning from Omicron How to Live With the Virus in the New Year

Author: Agnes Tandler

Since the start of the pandemic in 2020, Agnes Tandler has been based in Japan, where her reporting covers COVID-19 for a daily healthcare newsletter in Germany. Find other essays and reports for JAPAN Forward here.

You may like

-

Universal / Remote: Tokyo Art Exhibition is a Powerful Exploration of the Post-COVID World

-

Japan and CARICOM Friendship: Ties Going Strong in the Caribbean Sponsored

-

New Measles Cases Spark Concern, Health Ministry Urges Caution

-

'Cuteness in Space' as JAXA Carries Out the Serious Business of Its H3 Launch

-

Success as Second H3 Rocket Launched: What to Know

-

Full Support to Bring Japanese Abduction Victims Home, Says US Envoy

You must be logged in to post a comment Login